Wind tugging at my sleeve

feet sinking into sand

I stand at the edge where earth touches ocean

where the two overlap

a gentle coming together

at other times and places a violent clash.

–Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 1987

The shoreline is an unusual kind of boundary.1 Whereas most boundaries enforce separation, it is a threshold marked by contact and negotiation, change and instability. It is a place of arrivals and departures, of safe harbours and hostile intrusions. At once embedded in local traditions and subject to industrial development, it is a site of encounter between different populations and environments.

In the case of marine shorelines, the intertidal zone – exposed to the air at low tide and immersed in water at high tide – is an in-between realm of intermittent transformation, containing a high diversity of species that have found ways to survive together within the challenging flux of the ecosystem. As the planet heats up and water levels rise, the shoreline is among the places where our vulnerability to climate emergency is made most manifest.

Shoreline Movements2 is a film program that approaches the threshold between land and water as a material environment and as a provocative metaphor for the uncertainties and conflicts of worldly existence. By attending to the shifting frontier of the shoreline and the organisms that inhabit it, we can learn to think ecologically, which means understanding the fluid relations that exist between a vast array of agents, to the point that presumed separations between them are put into question.

Sometimes these relations are harmonious, but they can equally be characterized by discord and violence; the shoreline is where seemingly irreconcilable worlds confront one another in negotiations without end.

Across eighteen works of cinematic non-fiction made between 1944 and 2020, Shoreline Movements3 explores how artists and filmmakers have addressed the manifold encounters that take place in the littoral zone, broaching issues of environmental crisis, indigeneity, coloniality, community, and otherness. Presented within a space designed by Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, across six cycles that come and go like the tides, these films search for ways to render sensible the particularity and complexity of reality, embracing filmic and verbal language as nontransparent mediators that aid in this task. Through a wide range of strategies – from observation and the interview to speculative fiction and the essay form – they confront the difficulty and the desirability of building a shared world when deep divisions and power asymmetries everywhere prevail. In the aftermath of harm and loss, they imagine possibilities of repair and resurgence.

Space

The architecture -the landscaping, the gardening- designed for Shoreline Movements tries to create a feeling of ‘outside’ inside the museum. In Taipei that was achieved through an open plaza and two small pavilions: entering the more private rooms and exiting into a small square created a circulation and a space of its own.4

Inspired by the irregular occupations often found in beach cities where populations grow exponentially in summer and leave the place vacant the rest of the year, or fisherman ports where abandoned boats and outdated fishing gears live in contrast with newer industrial extractive technologies, it seems that shorelines occupations are always in a simultaneous process of decay and reinvention, as in an entropic process affected by the liquidity of the water masses they neighbour.5

Similar to an open air cinema seance, common in popular summer fairs and village festivities, the scenography for Shoreline Movements share with this spaces a flexibility and spontaneous occupation by the visitors.

The floor covered in soil enhances the feeling of being outside and reveals the artifice of the museum walls that virtually - but also literally, brick by brick - have been placed to hold a fiction, that of how we represent ourselves.6

If an exhibition is an experiment to articulate reality, to confuse the inside and the outside of the exhibition is one of the first duties of art: the space of the museum cannot be longer a space for the mere accumulation of artifacts, isolated and protected from the outside, but a place where our relations with images and reality is reconfigured.

The importance relies in what happens when leaving those rooms and confronting reality again.

Program

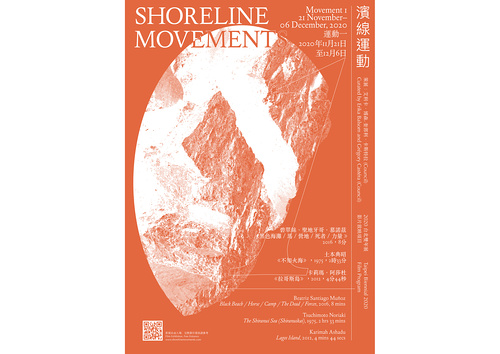

Movement 1 (21 November - 06 December 2020)

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Black Beach/Forces/The Dead/Camp, 2016, 8:00

Tsuchimoto Noriaki, The Shiranui Sea (Shiranuikai), 1975, 153:00

Karimah Ashadu, Lagos Island, 2012, 4:44

In 2003, following widespread protests, the United States Navy withdrew from Vieques, an island off the eastern coast of Puerto Rico that it had used since the 1940s for weapons testing and training, leaving behind serious environmental damage that many residents claim is responsible for the elevated rates of illness that exist in the area. Beatriz Santiago Muñoz attends to the reclaiming of this once militarized space by local communities as they fight for decontamination. She is a witness to their actions but refrains from any explanation, preferring instead to craft lyrical evocations of place. Black Beach / Forces / The Dead / Camp7 assembles a silent chorus dedicated to acts of repair, finding beauty and renewal amidst the ongoing trauma of expropriated and poisoned land.

In 1965, Noriaki Tsuchimoto8 initiated what would become a sustained practice of chronicling the socio-political, environmental, legal, and medical dimensions of mercury poisoning in and around Minamata Bay. Across some seventeen films, Tsuchimoto charted how methylmercury in the wastewater of a chemical factory owned by the Chisso Corporation decimated marine life and caused severe neurological problems and fatalities in those who ate the contaminated seafood. Made after Chisso was found guilty of corporate negligence in 1973, The Shiranui Sea explores how daily life went on in the area. Tsuchimoto does not shy away from the depiction of suffering and insists on accountability, while manifesting a tremendous capacity for listening and compassion. Human and non-human life are shown to be mutually interdependent, with both emerging as vulnerable to harm and resilient in its aftermath.

To create the disorienting experience of Lagos Island9, Karimah Ashadu built what she calls a “camera wheel mechanism”: made from found objects and inspired by the carts workers use to transport goods in Lagos, it is a contraption that holds her digital camera, enabling it to roll down the shore, endlessly changing perspective. Sand trades places with sky at variable speeds; all stable coordinates give way to flux. As the camera wheel passes the temporary settlements of migrants – soon to be torn down by the municipal authorities – this bricolage screeches and creeks, never ceasing to remind of the friction that undergirds its mobility. Ashadu refuses the detached stability that typically characterizes the camera’s gaze, insisting rather that the machine is an embedded part of a terrain subject to constant change.

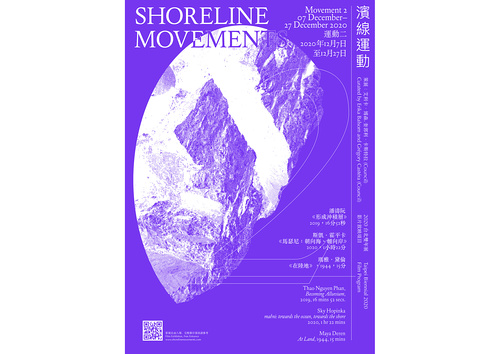

Movement 2 (07 December - 27 December 2020)

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019, 16:52

Sky Hopinka, maɬni – towards the ocean, towards the shore, 2020, 82:00

Maya Deren, At Land, 1944, 15:00

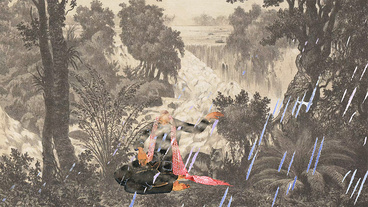

As an opening title puts it, Becoming Alluvium10 is a work “inspired by the beauty and suffering of the Mekong.” Drawing on Lao and Khmer folktales, as well as the writing of Italo Calvino, Marguerite Duras, and Rabindranath Tagore, Phan crafts a poetic allegory that addresses loss, reincarnation, and metamorphosis across three chapters with the river at their heart. The devastating collapse of a dam, everyday environmental degradation, and the desires of a princess to wear jewellery as beautiful as the monsoon dew come together to form a delicate evocation of the region and its syncretic culture.

Hopinka’s debut feature film limns a cyclical movement of death and rebirth. maɬni11 draws on the origin-of-death myth proper to the Chinookan people of the Pacific Northwest of the United States, in which Lilu (wolf) and T’alap’as (coyote) discuss the afterlife. Much of the film is spoken in Chinuk Wawa, a nearly extinct pidgin trade language that Hopinka, who belongs to the Ho-Chunk Nation, learned when he was in his twenties; when English is spoken, it is subtitled. Intimate conversations with Sweetwater Sahme and Jordan Mercier – each of them expectant parents and close friends of the filmmaker – are interwoven with a lyrical rendering of the land and water of the Columbia River Basin and an attention to the bonds between language and community, memory and resurgence.

At Land’s12 break with linear time is announced from the very beginning, when Maya Deren’s visionary protagonist emerges from the sea. She lays supine on its threshold as the waves strangely withdraw into themselves – a filmic trick of reverse motion. Deren was critical of what she termed the “horizontal time” of conventional narrative cinema, arguing instead for a poetic, vertical time that moves neither forward nor backward, but which condenses fragmentary affective states and associations. In At Land, space and time are freed from pre-given coordinates, as the liminal space of the beach grounds a drifting exploration of the vagaries of psychic life. Events are reshuffled according to an oneiric logic that draws no boundary between subjective states and objective reality.

Movement 3 (28 December 2020 - 17 January 2021)

Edith Dekyndt, Dead Sea Drawings (Part 1), 2010, 4:40

Joshua Bonnetta, The Two Sights, 2019, 90:00

Rebecca Meyers, blue mantle, 2010, 34:00

Holding a small sheet of blank paper under the surface of the Dead Sea, Edith Dekyndt13 registers the ephemeral refractions of light caused by the mineral content present in the saltwater. Through this simple gesture, what might have been presumed to be a clear emptiness is revealed to contain a fullness capable of generating delicate undulations, so many “drawings” that dissolve without a trace. Dekyndt’s piece of paper is a plane of projection, a screen upon which the normally hidden movements of the water become available to view, prompting a consideration of the limits of the visible and the apparatuses that inform our apprehension of the world.

In Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, an archipelago where many people still speak Scots Gaelic, the second sight is known as an dà shealladh: a form of experience occurring in excess of the first sight that most all possess, whereby one sees or hears premonitions of events to come, particularly those concerning death. The Two Sights14 relays the stories of such seers in voiceover, putting them in relation with images and sounds of the area, particularly its natural environment. Many of those who speak recall episodes from bygone years, some dating to before their birth, stories that – like the second sight itself – have been passed down through families. A number of them relay their accounts in Scots Gaelic, a language researchers predict will be extinct within a decade unless significant action is taken. The film makes no judgment as to whether the second sight is superstition or something more, preferring instead to engage in a labour of description. Bonnetta gives primacy to documenting five islands and listening to their inhabitants, raising the question of what connections exist between the faculty of the second sight and the maritime isolation of the Hebrides.

Filled with hypnotic images of the empty ocean, Meyers’s meditative film15 exquisitely renders the textures, colours, and all-over movements of the waves. The ocean appears as a vast emptiness. But as Herman Melville wrote in Moby Dick, “When beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it.” Meyers reminds us, putting her sublime visions of the oceanic expanse into dialogue with quotations and representations that attest to its rich history in a cultural repertoire of signs. She draws on American literature of the nineteenth century, monuments, paintings, and museum exhibitions to offer a portrait of the beauty and violence of the Massachusetts coast. The ocean is at once a blank void, an historical archive, a screen for the projection of the dreams and nightmares of those who remain on land.

Movement 4 (18 January - 07 February 2021)

Carlos Motta, Nefandus, 2013, 13:00

Hu Tai-li, Voices of Orchid Island, 1993, 73:00

Patricio Guzmán, The Pearl Button (El botón de nácar), 2015, 82:00

Two men travel down the Río Don Diego River in northern Colombia, one indigenous and the other Spanish-speaking. In voiceover, they tell of how the practice of sodomy was understood before and after the arrival of colonialists and the accompanying imposition of Christianity: the Spanish used it as a weapon of war, yet simultaneously condemned it as immoral. As their canoe moves through a landscape that betrays no hint of the atrocities it has witnessed, their reflections speak to how coloniality entails not just a conquest of territory but an importation of categories that reorganize ways of thinking, knowing, and acting. In the face of the violence and hypocrisy of this history, Nefandus16 asserts the persistence of indigenous epistemologies, reclaiming a pre-Hispanic past for the emancipatory potential it wields in the present. Motta crafts a parable of the threshold, putting into relation the encounter of two cultures and the encounter between two bodies.

“How do you feel about co-operating in this film?”17 Sitting on the beach with a small group of people who live on Orchid Island, just 45 nautical miles from Taiwan, Hu Tai-li opens her film with a question that immediately establishes one of its central concerns: what it means to make an image of the other. To her query, one man responds that the more anthropologists engage with the island’s indigenous Yami community, the more harm they do. Ever aware of this danger, Hu’s film is marked by its subtle confrontation with the violence that lurks within the ethnographic enterprise, reflecting on the relationship between photography and power, the colonial desire for authenticity, and the border between insider and outsider. After reckoning with the folkloric spectacle staged for tourists visiting the island, Hu turns her attention to the provision of medical care there, the daily lives of its inhabitants, and their fight against the disposal of nuclear waste.

For Patricio Guzmán, water is a medium of connection. Through this flowing motif, he creates of constellations of meaning that illuminate what is shared between the sea and the stars, as well as between the decimation of the indigenous tribes of Patagonia following the arrival of European settler-colonialists in the nineteenth century and those tortured and disappeared during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in the 1970s. Using interviews, archival materials, and spectacular depictions of landscape, The Pearl Button18 assembles an essayistic account of Chilean history that rejects heroic narratives of progress and national belonging. Guzmán dwells in an enduring grief for losses that remain too little acknowledged, finding possibilities for reparation and commemoration in the nonlinear temporalities of cinematic montage.

Movement 5 (08 February - 21 February 2021)

Jessica Sarah Rinland, Y Berá – Bright Waters, 2016, 9:37

Ben Rivers, Slow Action, 2011, 45:00

Johan van der Keuken, Flat Jungle (De platte jungle), 1978, 90:00

Taking their name from the Guaraní “ý berá,”19 meaning “bright waters,” Argentina’s Iberá Wetlands are the second largest such environment in the world, comprising some 1.3 million hectares of swamps, lagoons, and marshes. Rinland presents lush 16mm images of the flora and fauna of the region, accompanied by a voiceover and on-screen titles that draw from a range of sources: biologists involved in re-introducing animals to the area, Argentinian writers such as the nineteenth-century naturalist Guillermo Enrique Hudson, local knowledge, and the internet. In a critical mimicry of the conventions of the nature documentary, Rinland orchestrates a confrontation between competing ways of making sense of the world, putting pressure on the genre’s pretensions to objective explanation. Prying open the space between picture and text, she gestures to the impossibility of producing a description that would fully and faithfully account for the described.

Filmed using a Bolex 16mm camera in four distant locations and taking its title from Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species, Slow Action20 makes use of a speculative conceit to transform documentary images of landscape into visions of a drowned world. The film’s narration, authored by science-fiction writer Mark von Schlegell, transports us to a time when water has flooded the planet’s land masses, forming a new geography of island societies. Aping the conventions of travelogue writing, Slow Action’s voiceovers relay the unique characteristics of four utopian societies that took shape in complete isolation, accompanied by images of real locations: Lanzarote in the Canary Islands; Tuvalu in the South Pacific; Gunkanjima, an abandoned island off the coast of Nagasaki; and Rivers’s native Somerset. In the space between sound and image, Rivers creates a fictional atlas of future ruins that is equally anchored in our fragile present.

Flat Jungle21 embraces dramatic shifts of scale, moving between the microscopic and the immense to document an intertidal zone of wetlands in the north of the Netherlands at a time when the region was undergoing rapid industrialization and community protests against nuclear power. Reflecting on the film, van der Keuken explained, “I wanted to concentrate on the people who live on the Wadden Sea’s shores to reach an understanding of nature through them. For me, the emphasis is on vitality, contradictions, directness. I would be very satisfied if this film could make some contribution towards making more people aware that it is in their own interest that an area such as the Wadden Sea is safeguarded. This means that we must try to disprove the supposed conflict of interests between the conservation of nature on the one hand and the well-being of the workers on the other. This task is so difficult that even a partial success on this score would be very welcome.”

Movement 6 (22 February - 14 March 2021)

Peggy Ahwesh, The Blackest Sea, 2016, 9:30

Francisco Rodriguez, A Moon Made of Iron (Una luna de hierro), 2017, 29:00

Zhou Tao, The Worldly Cave, 2017, 47:53

In The Blackest Sea22, Ahwesh transforms animated news clips produced by the Taiwanese company TomoNews into an eerie indictment of contemporary existence and, more particularly, the circulation and consumption of images of crisis. Accompanied by the melancholic grandeur of Ellis B. Kohs’s “Passacaglia for Organ and Strings,” appropriated images of oceanic emergency unfurl: water is contaminated, schools of fish float dead to the surface, and boats of migrants capsize at sea. Here, Ahwesh protests the airbrushing of reality, what she has called “the cutefication of our world,” and probes the role images play in alternately fortifying or corroding a belief in a shared reality. Recognizable images of recent atrocities reappear as digital animations drained of specificity, as Ahwesh questions the easy digestibility of that which should sear our minds and stick in our throats.

A Moon Made of Iron23 opens with the poetry of Xu Lizhi, a worker at the Foxconn electronics factory in Shenzhen, China, who committed suicide in 2014 at the age of 24. It then cuts across the globe to the waters of Patagonia. The sea appears placid, but it is in fact a sea of desperation, horrendous working conditions, and bodies overboard in liquid graves. Moving between the local and the global, the shore and the deep, Francisco Rodriguez inhabits the rippling wake of dead Chinese workers who attempted to flee their squid-fishing boat off the Chilean coast, far from the first for whom a long maritime voyage was one of no return. In Una luna de hierro, the distant is near and the near, distant.

The Worldly Cave24 takes its name from a village, Fán Dòng, in Shaoguan, China, that ceased to exist when mining companies forced its inhabitants to relocate elsewhere. No images of this village appear in The Worldly Cave, but the spectre of displacement and the transformative impact of industry on the land weigh heavily on its otherworldly visions. Dispensing with narrative altogether, Zhou follows the diasporic trajectories of the Hakka people around the world, filming in disparate locations, including the Sonoran Desert in the United States, the island of Menorca in Spain, and the port of Incheon in South Korea. Stripped of identifying characteristics that would anchor them in a particular geography, these uncanny images mix the referential and the synthetic, upending habitual expectations of scale and figure-ground relationships.

A project by

- Council

Curated by

- Erika Balsom

- Grégory Castéra

Spatial design by

- Daniel Steegmann Mangrané

Films by

- Peggy Ahwesh

- Karimah Ashadu

- Joshua Bonnetta

- Edith Dekyndt

- Maya Deren

- Patricio Guzmán

- Sky Hopinka

- Hu Tai-li

- Johan van der Keuken

- Rebecca Meyers

- Carlos Motta

- Beatriz Santiago Muñoz

- Thao Nguyen Phan

- Jessica Sarah Rinland

- Ben Rivers

- Francisco Rodriguez

- Tsuchimoto Noriaki

- Zhou Tao

Poster design by

- Lu Liang

Assistant

- Yundi Wang

Cover and top image: film stills from Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019-ongoing, single-channel colour video, 16 mins, 50 seconds, courtesy the artist

On the occasion of

- Taipei Biennial 2020

- curated by Bruno Latour and Martin Guinard

On becoming earthlings is Supported by

- Carasso Foundation

Council is supported by

- Foundation for Arts Initiatives