Dear reader,

I have a feeling of sadness thinking that The Against Nature Journal is closing down after three really fantastic issues. They sit prominently on the bookshelf in my office and inevitably some curious visitors pick them and gasp about how beautiful the publication is!

The journal is so aesthetically pleasing that rarely visitors can resist gently turning the pages and savoring the feel of the paper, the beauty of the art and the fineness of the production. The experience of the object leads to a content which traverses so many domains – art, literature, activism, law, medicine and the archives. For those with a curiosity about the world, an interdisciplinary cast of mind and a desire to move beyond narrow disciplinary walls, the journal was a blessing.

Going back to the founding moments, I was so in- trigued by the proposal by Grégory and Aimar to tell the story of the idea of “nature”. In my own work as a lawyer challenging Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, I had engaged closely with what the law considered, “against the order of nature.” However, the proposal for the journal piqued my curiosity to go beyond the legal to approach a multi-disciplinary standpoint.

I loved the fact that the journal took activism seri- ously as a starting point. It provided a wonderful platform for activists from around the world to debate these laws and to celebrate their aesthetic, cultural, legal and academic interventions.

It also took history and the archive seriously. It was fascinating to be brought back to the story of sodomy in New Spain in the 16th century and India in colonial times. These juxtapositions jogged one’s mind down new pathways and for that I will be grateful to the editors.

While I write this, my sadness is increasingly tinged with a feeling of happiness at what the team has accomplished in

these three issues. The journal has opened out a new space for think- ing about “against nature” and I am sure the ideas gathered in the three issues will find new homes!

What is the future I can see for the journal? It would be lovely to see copies in LGBTQI+ spaces, lawyers offices, artist spaces as well as public libraries. By their quiet but inviting presence, one hopes that new generations of activists, academics, artists as well as the curious reader will feel impelled to open the pages and begin a journey of understanding one of the most significant topics of our times, namely, why do people suffer discrimination on the ground that their sexual conduct is against the “order of nature.”

Arvind Narrain

Dear reader,

I am reading back over the three issues of the journal, contemplating how to say goodbye to this project. My endless love and gratitude for people who edit collections of all kinds – journals, anthologies, zines – is present. It is a labor of love, working with many different contributors through the editorial process, through the deadlines and extensions, imagining the ways that all these thinkers will braid together for readers, always way more than the sum of their parts. Collections like this have been essential to my political development, letting me think in new ways, constituting new communities of writ- ers and thinkers. The level of concentrated intention and attention in how the issues of The Against Nature Journal come together lands so profoundly in me, makes me think about what practicing queer/trans internationalist solidarity-based politics means and feels like. Reading frank, painful, rigorous accounts of the daily operations of heteropa- triarchy in various contexts from people who are caring and resisting, and refusing pinkwashing, progress narratives, and one-dimensional stories of victimization, stirs in me a sense of connection and possi- bility that national borders and militaries seek to restrain.

Upon re-reading, there are some key questions I am contemplating, questions towards which the three issues of T.A.N.J.

provide helpful inroads. How do we engage with the brutal interactions of anti-queer, anti-sex, racist, capitalist legal systems while refusing to seek answers through the empty promises of rights discourse? How do we shape resistance practices based in the understanding that freedom and liberation cannot be delivered by governments, which exist for domination, but instead through ungovernable, unruly practices of or- dinary people? How are the disasters we are living through – caused by pandemics, climate change, wealth concentration, and war-generating new understandings of how queer and trans liberation is practiced through autonomy, through attacking and dismantling extractive sys- tems, instead of negotiating, requesting, or collaborating with them? How do we engage with legal systems that are devouring and killing our people without ending up in system-sustaining reformist struggles to improve and correct them?

I look forward to continuing to find all the editors, contributors and readers of T.A.N.J. in other spaces to tussle over these and many other questions together. Grateful to all for this project.

Love,

Dean Spade

Dear reader,

The first book I ever read that I could consider to be queer (not count- ing certain children’s books of illustrated bible stories) was an English translation of Against Nature (A rebours) by J.-K. Huysmans, origi- nally published in 1884. I was about fourteen at the time, as I remem- ber, very much a recluse myself, as much as a schoolboy can be, buried in my books, which I poured over night and day. And so this book, by a recluse, a kind of inventory of his fascinations, and his obsessions, and his sensory compulsions, all described with the oversensitive delicacy of the over-educated (is it possible to be over-educated?) botanist, became a sudden something to cling to, a glimpse of another world that might be mine... not his world, exactly, but something equally constructed that might be mine. What would that construction be?

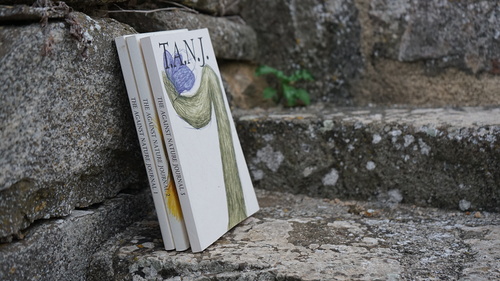

And now, at the age of seventy-six, I have in my hands three issues of the journal T.A.N.J. (The Against Nature Journal).

I have thought a lot about these three volumes, what binds them as a single publication. It could lead me very quickly down a path about publishing itself, for example about Andy Warhol’s Interview, that period when Richard Bernstein supplied the heavily formatted cov- ers – always portraits, not quite photographs, always highly colored and in fact the ONLY color in the magazine. Or General Idea’s FILE Magazine from the same period, with heavily formatted color covers that transformed a tabloid newspaper into a magazine. In a way FILE and Interview were both drag queens of the publishing world. What they hid was as important as what they revealed, and there was lots of winking going on.

T.A.N.J. is similarly impenetrable. It holds its simple little pencil-crayon cover like a sheath, tightly about its body. I may be cheap, it seems to say, but I am sophisticated too, intellectually rigorous even. And this isn’t just any card cover wrapped coyly around me. Please look carefully, all ye who enter here.

I could take this comparison further: the Table of Contents, for example, the way T.A.N.J. interpolates different types of contents: “Questionnaire”, “Reader”, “Poem”, and even “Artist Commission.” I won’t go into this too much now: it is late, I am sleepy, and I am already past my deadline. But (hopefully) you get the idea. It’s like Ed Sullivan wearing pajamas for a special children’s hour.

But alas, all good things must come to an end. So too with T.A.N.J. I don’t feel that is a problem. It is already a perfect Trinity. Why mess with something that is already sublime? My congratulations go out to all who participated in this self-styled “intersection”-made- object. Bravo!

AA Bronson

Dear reader,

It is bitter-sweet for me to bid farewell to the editors, publishers, academic scholars, lawyers, judicial officers, human rights activists, artists, writers, poets, photographers, film makers and readers gathered around the fires of The Against Nature Journal. The three issues published are worth celebrating.

T.A.N.J. was a multiple-media, trans-disciplinary, mixed-genre and transnational platform. Myriad themes were covered including intersections between legislation, human rights activism, spirituality and religions in the first issue, migration, forced displace- ment of LGBTIQ from contexts of criminalisation, homelessness

and migration in the second issue, and how medicine pathologizes non-procreative sexual desire in the third and last.

T.A.N.J.’s central concern of exploring “crimes against nature” laws and their legacies demanded urgency, particularly because of paradoxical global developments. While some countries were decriminalising same-sex sexualities and non-conforming gender identities, sixty-seven other countries were simultaneously practising the criminalisation and re-criminalisation of some forms of same-sex behaviour through new legislations or amending existing national laws. Penalties range from monetary fines to prison sentences, life imprisonment and the death penalty. Moreover, nine countries crim- inalise forms of gender expression targeting transgender and gender non-conforming people. Furthermore, activism, education, communi- cation and transfer of information about LGBTIQ people is outlawed in some contests prohibiting “propaganda supporting LGBTIQ” or “promotion of homosexuality.” This discrimination on grounds of non-heteronormative sexual orientation and non-conforming gender identities diffuses into inequality and violation against human rights including education, health, housing, employment, justice, safety, security, civil and political participation, community belonging, free expression, freedom of association and assembly.

Worrying global developments of the resurgence of fundamentalist movements and conservative right-wing forces repack- aged in diverse forms of anti-gender advocates highlight the urgent need for a space devoted to discussion, debate and dialogue about furthering the fight against “crimes against nature”. It is my prayer and hope that T.A.N.J. will return to us and continue playing its vital role of knowledge production about this broad topic.

Sincerely,

Stella Nyanzi

Dear reader,

The Against Nature journal (T.A.N.J.) is a small fragment of another world, a world that is also our world. It is a fragment made up of fragments, like the tes- serae of mosaics that give us startlingly colored glimpses into worlds not our own, glimpses of possibilities that were and are and might be again.

Within the multiple worlds of the violence committed against those whose lives are designated contra naturam, there are other worlds that are here, in our midst, already. The journal was launched at the start of the pandemic and destroyed by it, yet the three issues remain, like small fragments. They are beautiful objects, even reverent. The materiality of the journal displays the respect and care T.A.N.J. evinces for its subjects and contributors, the messy, unwieldy, and gorgeous not-collective that is a queer “we”. Opting for a material object invites multiple temporalities of engagement: dipping into an issue for a moment or two, staying with it for a period of time measured by the sips that empty a mug of tea, returning to it as its pages become dogeared, marked by fingerprints stained with lipstick or turmeric or the sweat of a lover.

The journal’s queer “we” emerges across its pages, in moments of recognition and discovery – an artist I have heard of, an activist I have not, a collective I want to learn from, a book or magazine I want to find. The anticipatory temporality of possibility, the hope encoded in these pages, remains.

Small fragments:

“Viruses are not the only things that incubate in groups, so does creativity, debate, inspiration, desire, and fear.”

(Maya Mikdashi, issue #1)“When [mother] thinks she might for the first time experience a hug, and does not. And then, later on, she does, from the woman for whom she has given birth, who does not have a uterus.”

(Indrapramit Das, issue #3)“Evermore Muzariri’s (pseudonym) description of how he feels working for other asylum seekers in South Africa: “I haven’t lost hope. ... I am very, very happy.”

(Carl Collison, issue #2)

We had religion, migration, medicine. We will not have love, death, nature, the lenses intended for the next three issues. The somatic time of the pandemic remains; we have suffered uncountable losses. T.A.N.J. is among them, yet not without trace. The worlds made and reflected within these pages are also lesson plans – not blueprints for the revolution, but practical dream-infused models for changing what needs to be changed while naming and honoring what is and has been. The fleshy thoughts, experiences, and actions that are recounted in these pages, whose recounting is also a work of love. And so they remain, these small frag- ments that open up (our) worlds, and have a life yet to come.

Linn Marie Tonstad

Authors

- AA Bronson

- Arvin Narrain

- Stella Nyanzi

- Dean Spade

- Linn Marie Tonstad